Automatic HTTPS

Caddy is the first and only web server to use HTTPS automatically and by default.

Automatic HTTPS provisions TLS certificates for all your sites and keeps them renewed. It also redirects HTTP to HTTPS for you! Caddy uses safe and modern defaults -- no downtime, extra configuration, or separate tooling is required.

Here's a 28-second video showing how it works:

Menu:

- Overview

- Activation

- Effects

- Hostname requirements

- Local HTTPS

- Testing

- ACME Challenges

- On-Demand TLS

- Errors

- Storage

- Wildcard certificates

- Encrypted ClientHello (ECH)

Overview

By default, Caddy serves all sites over HTTPS.

- Caddy serves IP addresses and local/internal hostnames over HTTPS using self-signed certificates that are automatically trusted locally (if permitted).

- Examples:

localhost,127.0.0.1

- Examples:

- Caddy serves public DNS names over HTTPS using certificates from a public ACME CA such as Let's Encrypt

or ZeroSSL

.

- Examples:

example.com,sub.example.com,*.example.com

- Examples:

Caddy keeps all managed certificates renewed and redirects HTTP (default port 80) to HTTPS (default port 443) automatically.

For local HTTPS:

- Caddy may prompt for a password to install its unique root certificate into your trust store. This happens only once per root; and you can remove it at any time.

- Any client accessing the site without trusting Caddy's root CA certificate will show security errors.

For public domain names:

- If your domain's A/AAAA records point to your server,

- ports

80and443are open externally, - Caddy can bind to those ports (or those ports are forwarded to Caddy),

- your data directory is writeable and persistent,

- and your domain name appears somewhere relevant in the config,

then sites will be served over HTTPS automatically. You won't have to do anything else about it. It just works!

Because HTTPS utilizes a shared, public infrastructure, you as the server admin should understand the rest of the information on this page so that you can avoid unnecessary problems, troubleshoot them when they occur, and properly configure advanced deployments.

Activation

Caddy implicitly activates automatic HTTPS when it knows a domain name (i.e. hostname) or IP address it is serving. There are various ways to tell Caddy your domain/IP, depending on how you run or configure Caddy:

- A site address in the Caddyfile

- A host matcher at the top-level in the JSON routes

- Command line flags like

--domainor--from - The automate certificate loader

Any of the following will prevent automatic HTTPS from being activated, either in whole or in part:

- Explicitly disabling it via JSON or via Caddyfile

- Not providing any hostnames or IP addresses in the config

- Listening exclusively on the HTTP port

- Prefixing the site address with

http://in the Caddyfile - Manually loading certificates (unless

ignore_loaded_certificatesis set)

Special cases:

- Domains ending in

.ts.netwill not be managed by Caddy. Instead, Caddy will automatically attempt to get these certificates at handshake-time from the locally-running Tailscaleinstance. This requires that HTTPS is enabled in your Tailscale account

and the Caddy process must either be running as root, or you must configure

tailscaledto give your Caddy user permission to fetch certificates.

Effects

When automatic HTTPS is activated, the following occurs:

- Certificates are obtained and renewed for all qualifying domain names

- HTTP is redirected to HTTPS (this uses HTTP port

80)

Automatic HTTPS never overrides explicit configuration, it only augments it.

If you already have a server listening on the HTTP port, the HTTP->HTTPS redirect routes will be inserted after your routes with a host matcher, but before a user-defined catch-all route.

You can customize or disable automatic HTTPS if necessary; for example, you can skip certain domain names or disable redirects (for Caddyfile, do this with global options).

Hostname requirements

All hostnames (domain names) qualify for fully-managed certificates if they:

- are non-empty

- consist only of alphanumerics, hyphens, dots, and wildcard (

*) - do not start or end with a dot (RFC 1034)

In addition, hostnames qualify for publicly-trusted certificates if they:

- are not localhost (including

.localhost,.local,.internaland.home.arpaTLDs) - are not an IP address

- have only a single wildcard

*as the left-most label

Local HTTPS

Caddy uses HTTPS automatically for all sites with a host (domain, IP, or hostname) specified, including internal and local hosts. Some hosts are either not public (e.g. 127.0.0.1, localhost) or do not generally qualify for publicly-trusted certificates (e.g. IP addresses -- you can get certificates for them, but only from some CAs). These are still served over HTTPS unless disabled.

To serve non-public sites over HTTPS, Caddy generates its own certificate authority (CA) and uses it to sign certificates. The trust chain consists of a root and intermediate certificate. Leaf certificates are signed by the intermediate. They are stored in Caddy's data directory at pki/authorities/local.

Caddy's local CA is powered by Smallstep libraries

Local HTTPS does not use ACME nor does it perform any DNS validation. It works only on the local machine and is trusted only where the CA's root certificate is installed.

CA Root

The root's private key is uniquely generated using a cryptographically-secure pseudorandom source and persisted to storage with limited permissions. It is loaded into memory only to perform signing tasks, after which it leaves scope to be garbage-collected.

Although Caddy can be configured to sign with the root directly (to support non-compliant clients), this is disabled by default, and the root key is only used to sign intermediates.

The first time a root key is used, Caddy will try to install it into the system's local trust store(s). If it does not have permission to do so, it will prompt for a password. This behavior can be disabled in the configuration if it is not desired. If this fails due to being run as an unprivileged user, you may run caddy trust to retry installation as a privileged user.

After Caddy's root CA is installed, you will see it in your local trust store as "Caddy Local Authority" (unless you've configured a different name). You can uninstall it any time if you wish (the caddy untrust command makes this easy).

Note that automatically installing the certificate into the local trust stores is for convenience only and isn't guaranteed to work, especially if containers are being used or if Caddy is being run as an unprivileged system service. Ultimately, if you are relying on internal PKI, it is the system administrator's responsibility to ensure Caddy's root CA is properly added to the necessary trust stores (this is outside the scope of the web server).

CA Intermediates

An intermediate certificate and key will also be generated, which will be used for signing leaf (individual site) certificates.

Unlike the root certificate, intermediate certificates have a much shorter lifetime and will automatically be renewed as needed.

Testing

To test or experiment with your Caddy configuration, make sure you change the ACME endpoint to a staging or development URL, otherwise you are likely to hit rate limits which can block your access to HTTPS for up to a week, depending on which rate limit you hit.

One of Caddy's default CAs is Let's Encrypt

https://acme-staging-v02.api.letsencrypt.org/directory

ACME challenges

Obtaining a publicly-trusted TLS certificate requires validation from a publicly-trusted, third-party authority. These days, this validation process is automated with the ACME protocol

The first two challenge types are enabled by default. If multiple challenges are enabled, Caddy chooses one at random to avoid accidental dependence on a particular challenge. Over time, it learns which challenge type is most successful and will begin to prefer it first, but will fall back to other available challenge types if necessary.

HTTP challenge

The HTTP challenge performs an authoritative DNS lookup for the candidate hostname's A/AAAA record, then requests a temporary cryptographic resource over port 80 using HTTP. If the CA sees the expected resource, a certificate is issued.

This challenge requires port 80 to be externally accessible. If Caddy cannot listen on port 80, packets from port 80 must be forwarded to Caddy's HTTP port.

This challenge is enabled by default and does not require explicit configuration.

TLS-ALPN challenge

The TLS-ALPN challenge performs an authoritative DNS lookup for the candidate hostname's A/AAAA record, then requests a temporary cryptographic resource over port 443 using a TLS handshake containing special ServerName and ALPN values. If the CA sees the expected resource, a certificate is issued.

This challenge requires port 443 to be externally accessible. If Caddy cannot listen on port 443, packets from port 443 must be forwarded to Caddy's HTTPS port.

This challenge is enabled by default and does not require explicit configuration.

DNS challenge

The DNS challenge performs an authoritative DNS lookup for the candidate hostname's TXT records, and looks for a special TXT record with a certain value. If the CA sees the expected value, a certificate is issued.

This challenge does not require any open ports, and the server requesting a certificate does not need to be externally accessible. However, the DNS challenge requires configuration. Caddy needs to know the credentials to access your domain's DNS provider so it can set (and clear) the special TXT records. If the DNS challenge is enabled, other challenges are disabled by default.

Since ACME CAs follow DNS standards when looking up TXT records for challenge verification, you can use CNAME records to delegate answering the challenge to other DNS zones. This can be used to delegate the _acme-challenge subdomain to another zone. This is particularly useful if your DNS provider doesn't provide an API, or isn't supported by one of the DNS plugins for Caddy.

DNS provider support is a community effort. Learn how to enable the DNS challenge for your provider at our wiki.

On-Demand TLS

Caddy pioneered a new technology we call On-Demand TLS, which dynamically obtains a new certificate during the first TLS handshake that requires it, rather than at config load. Crucially, this does not require hard-coding the domain names in your configuration ahead of time.

Many businesses rely on this unique feature to scale their TLS deployments at lower cost and without operational headaches when serving tens of thousands of sites.

On-demand TLS is useful if:

- you do not know all the domain names when you start or reload your server,

- domain names might not be properly configured right away (DNS records not yet set),

- you are not in control of the domain names (e.g. they are customer domains).

When on-demand TLS is enabled, you do not need to specify the domain names in your config in order to get certificates for them. Instead, when a TLS handshake is received for a server name (SNI) that Caddy does not yet have a certificate for, the handshake is held while Caddy obtains a certificate to use to complete the handshake. The delay is usually only a few seconds, and only that initial handshake is slow. All future handshakes are fast because certificates are cached and reused, and renewals happen in the background. Future handshakes may trigger maintenance for the certificate to keep it renewed, but this maintenance happens in the background if the certificate hasn't expired yet.

Using On-Demand TLS

On-demand TLS must be both enabled and restricted to prevent abuse.

Enabling on-demand TLS happens in TLS automation policies if using the JSON config, or in site blocks with the tls directive if using the Caddyfile.

To prevent abuse of this feature, you must configure restrictions. This is done in the automation object of the JSON config, or the on_demand_tls global option of the Caddyfile. Restrictions are "global" and aren't configurable per-site or per-domain. The primary restriction is an "ask" endpoint to which Caddy will send an HTTP request to ask if it has permission to obtain and manage a certificate for the domain in the handshake. This means you will need some internal backend that can, for example, query the accounts table of your database and see if a customer has signed up with that domain name.

Be mindful of how quickly your CA is able to issue certificates. If it takes more than a few seconds, this will negatively impact the user experience (for the first client only).

Due to its deferred nature and the extra configuration required to prevent abuse, we recommend enabling on-demand TLS only when your actual use case is described above.

See our wiki article for more information about using on-demand TLS effectively.

Errors

Caddy does its best to continue if errors occur with certificate management.

By default, certificate management is performed in the background. This means it will not block startup or slow down your sites. However, it also means that the server will be running even before all certificates are available. Running in the background allows Caddy to retry with exponential backoff over a long period of time.

Here's what happens if there's an error obtaining or renewing a certificate:

- Caddy retries once after a brief pause just in case it was a fluke

- Caddy pauses briefly, then switches to the next enabled challenge type

- After all enabled challenge types have been tried, it tries the next configured issuer

- Let's Encrypt

- ZeroSSL

- After all issuers have been tried, it backs off exponentially

- Maximum of 1 day between attempts

- For up to 30 days

During retries with Let's Encrypt, Caddy switches to their staging environment

ACME challenges take at least a few seconds, and internal rate limiting helps mitigate accidental abuse. Caddy uses internal rate limiting in addition to what you or the CA configure so that you can hand Caddy a platter with a million domain names and it will gradually -- but as fast as it can -- obtain certificates for all of them. Caddy's internal rate limit is currently 10 attempts per ACME account per 10 seconds.

To avoid leaking resources, Caddy aborts in-flight tasks (including ACME transactions) when config is changed. While Caddy is capable of handling frequent config reloads, be mindful of operational considerations such as this, and consider batching config changes to reduce reloads and give Caddy a chance to actually finish obtaining certificates in the background.

Issuer fallback

Caddy is the first (and so far only) server to support fully-redundant, automatic failover to other CAs in the event it cannot successfully get a certificate.

By default, Caddy enables two ACME-compatible CAs: Let's Encrypt

Storage

Caddy will store public certificates, private keys, and other assets in its configured storage facility (or the default one, if not configured -- see link for details).

The main thing you need to know using the default config is that the $HOME folder must be writeable and persistent. To help you troubleshoot, Caddy prints its environment variables at startup if the --environ flag is specified.

Any Caddy instances that are configured to use the same storage will automatically share those resources and coordinate certificate management as a cluster.

Before attempting any ACME transactions, Caddy will test the configured storage to ensure it is writeable and has sufficient capacity. This helps reduce unnecessary lock contention.

Wildcard certificates

Caddy can obtain and manage wildcard certificates when it is configured to serve a site with a qualifying wildcard name. A site name qualifies for a wildcard if only its left-most domain label is a wildcard. For example, *.example.com qualifies, but these do not: sub.*.example.com, foo*.example.com, *bar.example.com, and *.*.example.com. (This is a restriction of the WebPKI.)

If using the Caddyfile, Caddy takes site names literally with regards to the certificate subject names. In other words, a site defined as sub.example.com will cause Caddy to manage a certificate for sub.example.com, and a site defined as *.example.com will cause Caddy to manage a wildcard certificate for *.example.com. You can see this demonstrated on our Common Caddyfile Patterns page. If you need different behavior, the JSON config gives you more precise control over certificate subjects and site names ("host matchers").

As of Caddy 2.10, when automating a wildcard certificate, Caddy will use the wildcard certificate for individual subdomains in the configuration. It will not get certificates for individual subdomains unless explicitly configured to do so.

Wildcard certificates represent a wide degree of authority and should only be used when you have so many subdomains that managing individual certificates for them would strain the PKI or cause you to hit CA-enforced rate limits, or if the privacy tradeoff is worth the risk of exposing that much of the DNS zone in the case of a key compromise. Note that wildcard certificates alone do not offer privacy of concealing specific subdomains: they are still exposed in TLS ClientHello packets unless Encrypted ClientHello (ECH) is enabled. (See below.)

Note: Let's Encrypt requires

Encrypted ClientHello (ECH)

Normally, TLS handshakes involve sending the ClientHello, including the Server Name Indicator (SNI; the domain being connected to), in plaintext. That's because it contains the parameters necessary for encrypting the connection that comes after the handshake. This, of course, exposes the domain name, which is the most sensitive part of the ClientHello, to anyone who can eavesdrop connections, even if they are not in your immediate physical vicinity. It reveals which service you are connecting to when the destination IP may serve many different sites, and it's how some governments censor the Internet.

With Encrypted ClientHello, the client can protect the domain name by wrapping the true ClientHello in an "outer" ClientHello that establishes parameters for decrypting the "inner" ClientHello. However, many moving parts need to come together perfectly for this to work and deliver actual privacy benefits.

First, the client needs to know what parameters, or configuration, to use to encrypt the ClientHello. This information includes a public key and "outer" domain (the "public name"), among other things. This configuration has to be published or distributed somehow in a reliable fashion.

You could theoretically write it down on a piece of paper and hand it out to everybody, but most major browsers support looking up HTTPS-type DNS records containing ECH parameters when connecting to a site. Hence, you will need to: (1) generate an ECH configuration (public/private key pair, among other parameters), and then (2) create an HTTPS-type DNS record containing the base64-encoded ECH configuration.

Or... you could let Caddy do that all for you. Caddy is the first and only web server that can automatically generate, publish, and serve ECH configurations.

Once the HTTPS record is published, clients will need to perform a DNS lookup for the HTTPS record when connecting to your site. Normally, DNS lookups are in plaintext, which compromises the security of the resulting ECH handshakes, so browsers will need to use a secure DNS protocol like DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) or DNS-over-TLS (DoT). Depending on the browser, this may need to be manually enabled.

Once the client has securely downloaded the ECH config, it uses the embedded public key to encrypt the ClientHello, and proceeds to connect to your site. Caddy then decrypts the inner ClientHello and proceeds to serve your site, without the domain name ever appearing in plaintext over the wire.

Deployment considerations

ECH is a nuanced technology. Even though Caddy completely automates ECH, many things need to be considered in order for maximum privacy benefits. You should also be aware of various trade-offs.

Publication

Caddy will only create an HTTPS record for a domain if there is already a record for that domain. This prevents breaking DNS lookups for a subdomain that may be covered by a wildcard. Ensure that your sites have at least an A/AAAA record pointing to your server. If you only use a wildcard for DNS records, then the wildcard domain will need to appear in your Caddy config as well.

Caddy will not publish an HTTPS record for a domain that has a CNAME record.

ECH GREASE

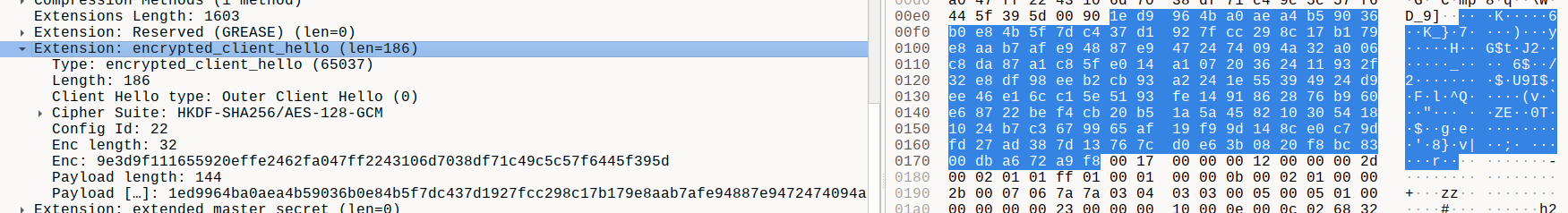

If you open Wireshark and then connect to any site (even one that does not support ECH) in a modern version of a major browser like Firefox or Chrome (even with ECH disabled), you may notice its handshake includes the encrypted_client_hello extension:

The purpose of this is to make true ECH handshakes indistinguishable from plaintext ones. If ECH handshakes looked different than normal ones, censors could just block ECH handshakes with minimal fallout/collateral damage. But if they blocked any handshake with a plausible ECH extension, they would essentially turn off most of the Internet. (The goal is to increase the cost of widespread censorship.)

This is mainly important to know when troubleshooting connections.

Key rotation

Like certificate keys, it is not good practice (and can be downright insecure) to use the same key for a long time. As such, ECH keys should be rotated on a regular basis. Unlike certificates, ECH configs don't strictly expire. But servers should rotate them nonetheless.

Key rotation is tricky though, because clients need to know about the updated keys. If the server simply replaced old keys with new ones, all ECH handshakes would fail unless clients were immediately notified about the new keys. But simply publishing the updated keys isn't enough. The reality is, DNS records have TTLs, and resolvers cache responses, etc. It can take minutes, hours, or even days for clients to query the updated HTTPS records and start using the new ECH config.

For that reason, servers should keep supporting old ECH configs for a period of time. Not doing so risks exposing server names in plaintext at scale.

However, that may not be enough. Some clients still won't get the updated keys for various reasons, and any time that happens, there is a risk of exposing the server name. So there needs to be another way to give clients the updated config in band with the connection. That's what the outer name is for.

Public name

The "outer" ClientHello is a normal ClientHello with two subtle differences that are only known to the origin server:

- The SNI extension is fake

- The ECH extension is real

That "outer" SNI extension contains the public name that protects your real domains. This name can be anything, but your server must be authoritative for the public name because Caddy will obtain a certificate for it.

If a client tries to make an ECH connection but the server can't decrypt the inner ClientHello, it can actually complete the handshake using the outer ClientHello with a certificate for the outer name. This secure connection is strictly only used to send the client the current ECH config; i.e. it is a temporary TLS connection for the sole purposes of completing the initial TLS connection. No application data is transmitted: just the ECH key. Once the client has the updated key, it can establish the TLS connection as intended.

In this manner, the true server name remains protected and out-of-sync clients remain able to connect, which are both vital elements of security.

The outer name may be one of your site's domains, a subdomain, or any other domain name that points to your server. We recommend choosing exactly one generic name. For example, Cloudflare serves millions of sites behind cloudflare-ech.com. This is important for increasing the size of your anonymity set.

Public names should not be empty; i.e. a public name must be configured for things to work. Caddy does not currently enforce this (and may later), but the ECH specification requires the public name to be at least 1 byte long. Some software will accept empty names, others won't. This can lead to confusing behaviors such as browsers using ECH but servers rejecting it as invalid; or browsers not using ECH (because it is invalid) even though the config is in the DNS record properly. It is the responsibility of the site owner to ensure proper ECH configuration and publication to ensure privacy.

Anonymity set

To maximize the privacy benefits of ECH, strive to maximize the size of your anonymity set. In essense, this set is comprised of client-facing servers that have identical behavior to observers. The idea is that an observer cannot easily reduce/deduce the possible sites or services clients are connecting to.

In practice, we recommend having only one public name for all your sites. (There is only 1 public name per ECH config, so this implies having only 1 active ECH config at any given time.) If you operate Caddy in a cluster, Caddy automatically shares and coordinates ECH configs with other instances, which takes care of this for you.

Taken to the extreme, this implies that every site on the Internet could or should be behind a single IP address and one public name...

Centralization

... which brings us to our next topic: centralization. One of the criticisms of ECH is that it tends to motivate centralization. It does this in at least two ways: (1) by clients favoring DoH/DoT for DNS lookups, which sends all DNS lookups through a small handful of providers, and (2) by maximizing the size of the anonymity set at scale.

When DoH or DoT is used, DNS lookups all go through the DoH/DoT provider. Between the client and the provider, the DNS data is encrypted, but between the provider and the DNS server, it is not encrypted. Global DoH/DoT effectively funnels all the juicy plaintext DNS traffic into a few big pipes that are ripe for observation... or failure.

Similarly, if we truly maximize the anonymity set at scale, all sites would be protected behind a single public name, like cloudflare-ech.com. This is good for privacy, but then the entire Internet is at the mercy of Cloudflare and that one domain name. Now, maximizing to that extent is not necessary or practical, but the theoretical implications remain valid.

We recommend each organization or individual choose a single name for all their sites and use that, and in most cases that should offer sufficient privacy. However, please consult experts with your your individual threat models for your specific case.

Subdomain privacy

With ECH, it is now theoretically possible to keep subdomains secret/private from side channels if deployed correctly.

Most sites do not need this, as, generally speaking, subdomains are public information. We advise against putting sensitive information in domain names. That said...

To avoid leaking sensitive subdomains to Certificate Transparency (CT) logs, use a wildcard certificate instead. In other words, instead of putting sub.example.com in your config, put *.example.com. (See Wildcard certificates for important information.)

Then, enable ECH in Caddy. A wildcard certificate combined with ECH should properly hide subdomains, as long as every client that tries to connect to it uses ECH and has a strong implementation. (You are still at the mercy of clients to preserve privacy.)

Enabling ECH

Since functioning ECH requires publishing configs to DNS records, you will need a Caddy build with a caddy-dns module plugged in for your DNS provider.

Then, with a Caddyfile, specify your DNS provider config in the global options, as well as the ECH public name you want to use:

{

dns <provider config...>

ech example.com

}

Remember:

- The DNS provider module must be plugged in and you must have the right configuration for your provider/account.

- The ECH public name should point to your server. Caddy will get a certificate for it. It does not have to be one of your site's domains.

If using JSON, add these properties to the tls app:

"encrypted_client_hello": {

"configs": [

{

"public_name": "example.com"

}

]

},

"dns": {

"name": "<provider name>",

// provider configuration

}

These configurations will enable ECH and publish ECH configs for all your sites. The JSON config offers more flexibility if you need to customize the behavior or have an advanced setup.

Verifying ECH

There is still not much tooling around ECH, so at time of writing, the best and most universal way to verify that it's working is to use Wireshark and look for your public name in the ServerName field.

First, start your server and see that the logs mention something like "published ECH configuration list" for your domains. (If you get any errors with publication, ensure your DNS provider module supports libdns 1.0 and file an issue with your provider's repository if you encounter problems.) Caddy should also get a certificate for the public name.

Next, make sure your browser has ECH enabled; this may require enabling DoH/DoT. It's also a good idea to clear your browser's (or system's) DNS cache, to ensure it will pick up the newly published HTTPS records. We also recommend closing the browser or at least opening a new private tab to ensure it does not reuse existing connections.

Then, open Wireshark and start listening on the appropriate network interface. While Wireshark is collecting packets, load your site in your browser. You can then pause Wireshark. Find your TLS ClientHello, and you should see the public name in the ServerName field, rather than the actual domain name you connected to.

Remember: you may still see an encrypted_client_hello extension even if ECH is not used. The key indicator is the SNI value. You should never see the true site name in plaintext with Wireshark if ECH is working properly.

If you encounter deployment issues with ECH, first ask in our forum. If it's a bug, you can file an issue on GitHub.

ECH in storage

ECH configurations are stored in the data directory in the configured storage module (the default being the file system) under the ech/configs folder.

The next folder is an ECH config ID, which are randomly generated and relatively unimportant. The randomness is recommended by the spec to help mitigate fingerprinting/tracking.

A metadata sidecar file helps Caddy keep track of when publications last occurred. This prevents hammering your DNS provider at every config reload. If you have to reset this state, you may safely delete the metadata file. However, this may also reset the time when the key will be rotated. You can also go into the file and clear out just the information about publication.